This post describes my implementation of Flushable SSTables in Pebble during my time at Cockroach Labs in 2022.

During my internship at Cockroach Labs, I spent a few months working on Pebble, CockroachDB's storage engine. One of the issues I tackled was a performance bottleneck in how Pebble ingested external SSTables. When these SSTables overlapped with in-memory data (memtables), the entire ingestion would stall until the in-memory data was flushed to disk.

At a high level, we revamp the ingestion pipeline to treat ingested SSTables as uniform with memtables; ingested data becomes immediately visible and gets flushed asynchronously.

As a result, we saw up to 75% faster ingestion while still maintaining the complex invariants associated with log-structured merge trees and SSTables.

The problem

SSTable ingestion is a common operation in CockroachDB. It's used for bulk imports, range rebalancing, backup restoration, schema migrations – basically anytime you need to move large amounts of data (SSTables) around without going through the normal write path.

The original implementation was as follows:

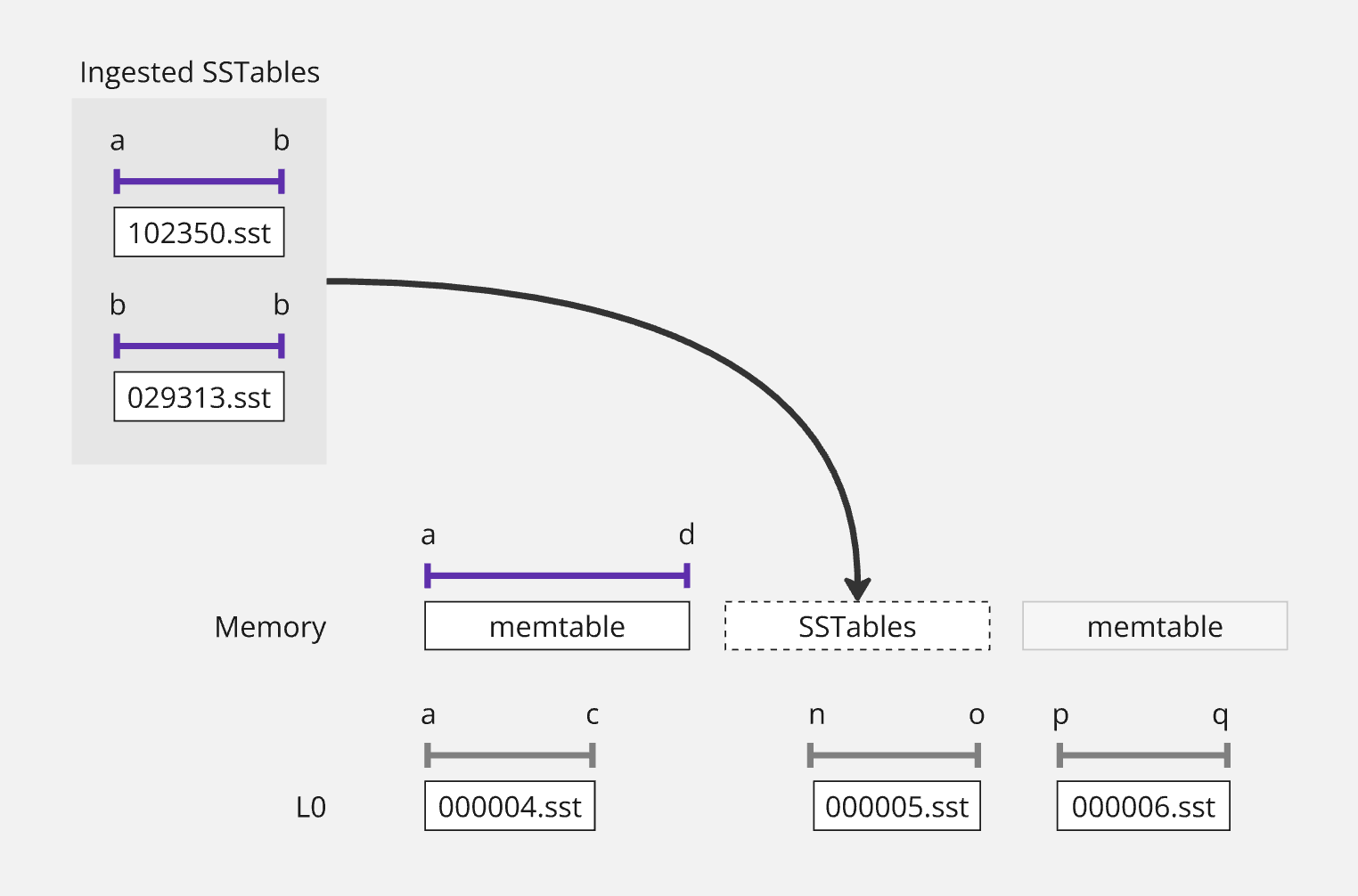

- When you ingest an SSTable, check if it overlaps with any in-memory data (memtables). If it does, wait for those memtables to flush to disk before proceeding.

Why did we need to block?

Ingested SSTables get sequence numbers newer than existing data (since they're newer data in the context of a database), but memtable data is newer, so it has to flush first. This ensures that the data in the ingested SSTables is ordered after the data in the memtables, which is necessary for maintaining the log-structured merge tree (LSM) sequence number ordering invariant.

If a memtable overlaps with your ingested SSTable's key range, your ingest needs to wait for the memtable to flush.

Here's what the original flow looked like:

1// Original ingestion flow (simplified) 2func (d *DB) ingest(paths []string) error { 3 // Analyze overlap with memtables 4 if d.hasMemtableOverlap(ssts) { 5 // BLOCKING: Wait for memtable flush to complete 6 if err := d.forceFlushMemtable(); err != nil { 7 return err 8 } 9 // Wait for flush job completion and manifest update 10 d.waitForFlushCompletion() 11 } 12 13 // Only now can we add SSTable to LSM 14 return d.addToLSM(ssts) 15}

In high-throughput scenarios, this would temporarily pause writes for 200-500ms. Even worse, if you had multiple overlapping memtables (which was common), each one needed to flush before ingestion could proceed!

The optimization

The key insight is that ingested SSTables and memtables are basically the same kind of thing: sorted, immutable batches of data that ultimately need to be incorporated into the LSM tree.So instead of treating them differently and paying the cost of waiting for memtables to flush, we can transform ingested SSTables into "flushable" entities – just like memtables. They get added to the flush queue and become immediately visible to reads, but their final placement in the LSM happens asynchronously.

How it works

The approach needed to satisfy three requirements, immediate visibility, existing flush codepaths, and crash safety:

- Reads should be able to see ingested data right away, even before it's flushed

- Memtables and ingested SSTables should flow through the same flush machinery for consistency

- Everything needs to survive crashes with the same durability guarantees as regular writes

The flushable interface

Pebble already had this interface for things that can be flushed:

1type flushable interface { 2 newIter(o *IterOptions) internalIterator 3 newFlushIter(o *IterOptions, byteInterval keyspan.Interval) internalIterator 4 newRangeDelIter(o *IterOptions) keyspan.FragmentIterator 5 inuseBytes() uint64 6 totalBytes() uint64 7 readyForFlush() bool 8}

Ingested SSTables have some very convenient properties:

- They're sorted

- They're immutable

- They have well-defined iterators

So I just needed to implement the interface and they'd functionally fit into the existing flush infrastructure.

Implementation

1// ingestedFlushable wraps ingested SSTables as flushable entities 2type ingestedFlushable struct { 3 files []*fileMetadata // Metadata for ingested files 4 cmp Compare // Key comparator 5 newIters tableNewIters // Iterator factory 6 slice manifest.LevelSlice // Virtual level slice 7 logNum base.DiskFileNum // Associated WAL number 8 exciseSpan KeyRange // Excised key range (if any) 9} 10 11func (f *ingestedFlushable) newIter(o *IterOptions) internalIterator { 12 // Create a level iterator over the ingested files 13 return newLevelIter(o, f.cmp, f.newIters, f.slice.Iter()) 14} 15 16func (f *ingestedFlushable) readyForFlush() bool { 17 // Always ready - files are already on disk 18 return true 19} 20 21func (f *ingestedFlushable) inuseBytes() uint64 { 22 // Return total size of ingested files 23 var size uint64 24 for _, file := range f.files { 25 size += file.Size 26 } 27 return size 28}

This gave us:

- Immediate visibility: Reads could access ingested data right away through the flushable's iterator interface

- Zero copy: No data movement – the SSTable files were already on disk

- Ordering preservation: The flush queue maintained proper sequence number ordering

How it actually works

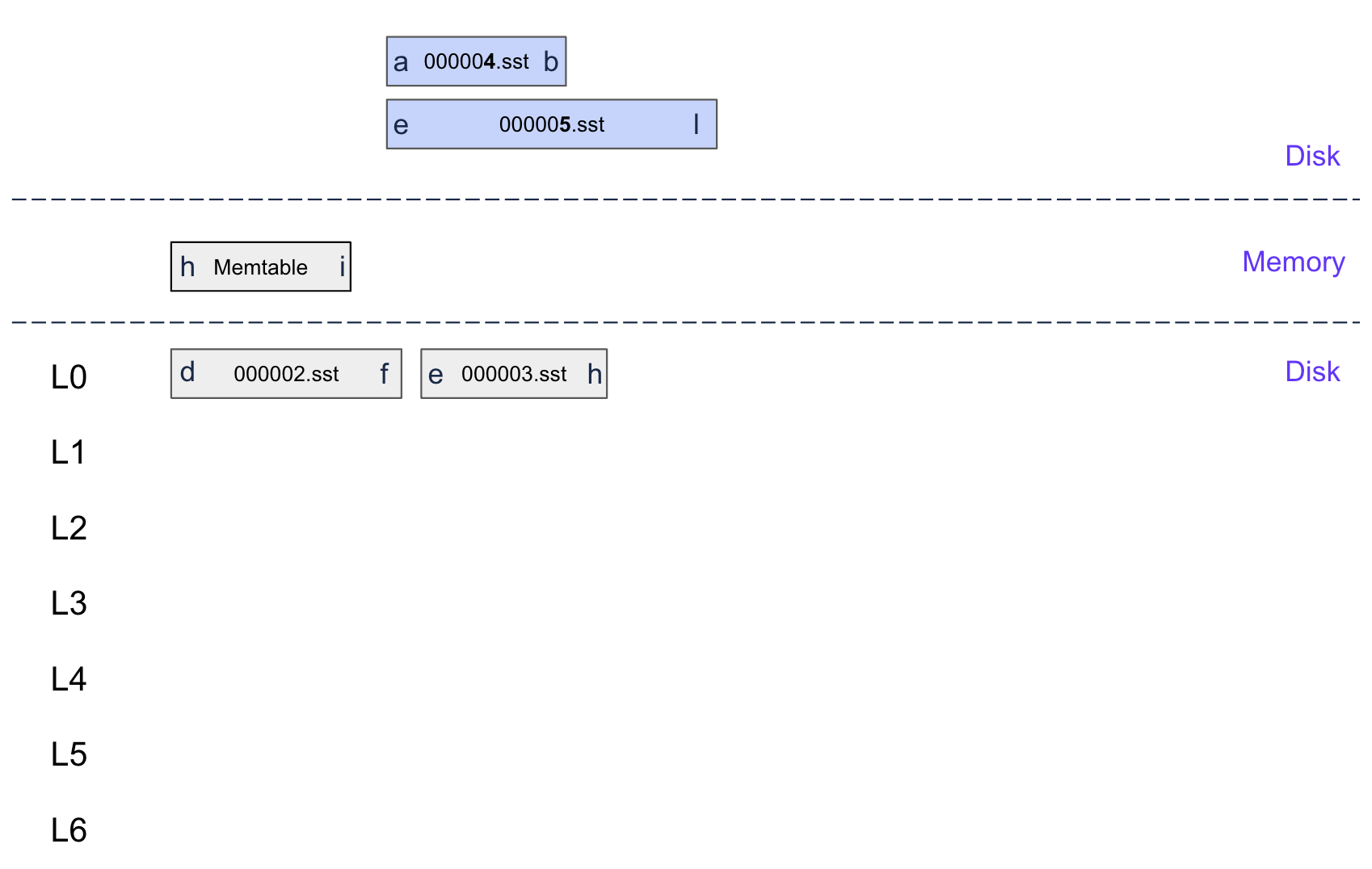

Let's walk through a concrete example. Say we have a memtable with keys H-I and we need to ingest an SSTable with ranges A-B and E-L.

Step 1: Detect overlaps

First, we figure out which memtables overlap with the ingested SSTable:

1func (d *DB) analyzeIngestOverlaps(meta []*fileMetadata) (overlaps []overlapInfo, err error) { 2 d.mu.Lock() 3 defer d.mu.Unlock() 4 5 for i, file := range meta { 6 // Check overlap with mutable memtable 7 if d.hasMemtableOverlap(file, d.mu.mem.mutable) { 8 overlaps = append(overlaps, overlapInfo{ 9 fileIndex: i, 10 memtable: d.mu.mem.mutable, 11 keyRange: file.UserKeyBounds(), 12 }) 13 } 14 15 // Check overlap with immutable memtables 16 for _, imm := range d.mu.mem.queue { 17 if d.hasMemtableOverlap(file, imm.flushable) { 18 overlaps = append(overlaps, overlapInfo{ 19 fileIndex: i, 20 memtable: imm.flushable, 21 keyRange: file.UserKeyBounds(), 22 }) 23 } 24 } 25 } 26 27 return overlaps, nil 28} 29 30func (d *DB) hasMemtableOverlap(file *fileMetadata, mem flushable) bool { 31 iter := mem.newIter(nil) 32 if iter == nil { 33 return false 34 } 35 defer iter.Close() 36 37 // Efficient range overlap test using iterator bounds 38 iter.First() 39 iter.Last() 40 return d.cmp(file.Smallest.UserKey, iter.Key().UserKey) <= 0 && 41 d.cmp(file.Largest.UserKey, iter.Key().UserKey) >= 0 42}

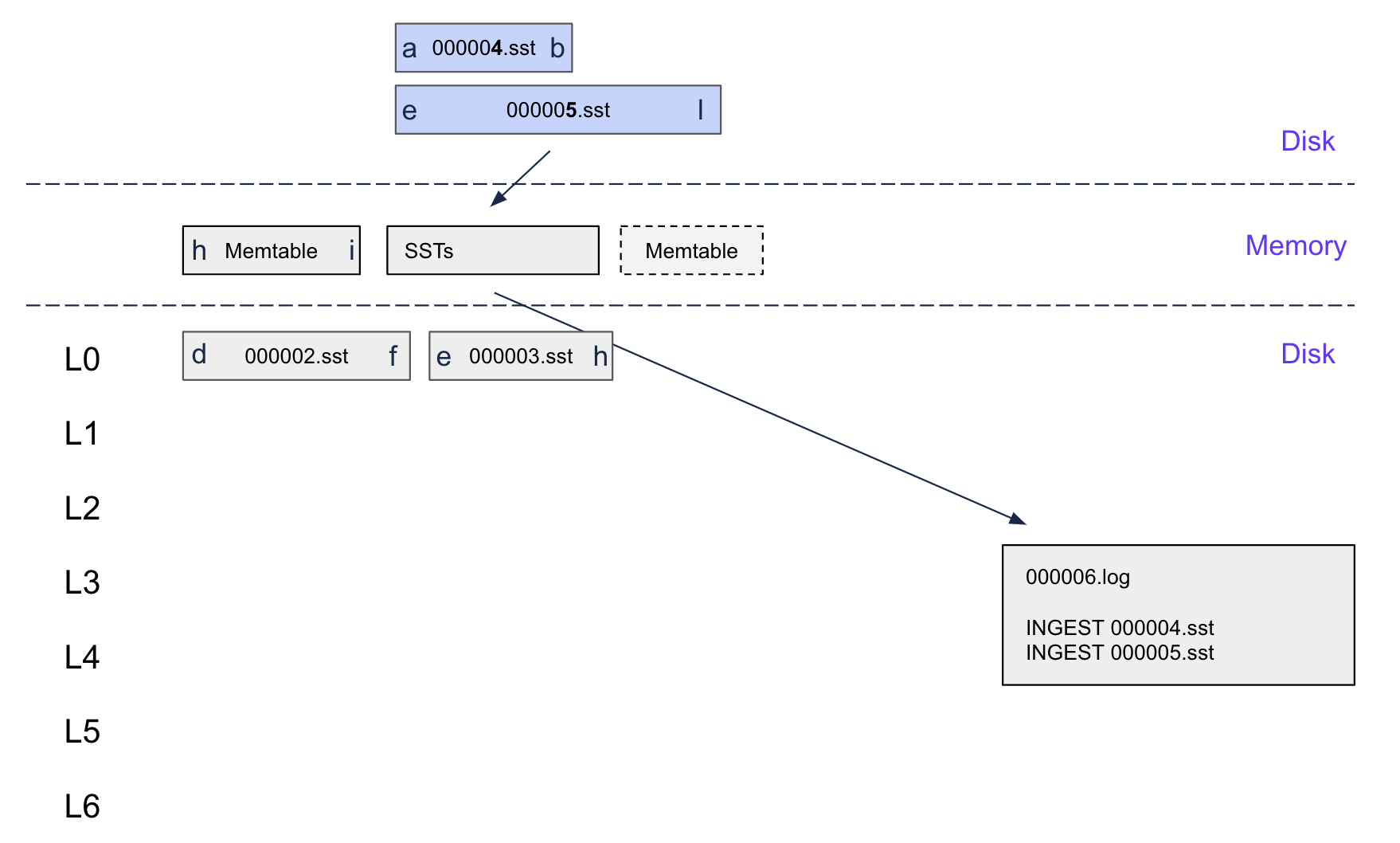

Step 2: Log it in the WAL

Before changing any state, we log the ingestion operation to the write-ahead log for crash recovery:

1func (d *DB) recordIngestOperation(paths []string, seqNum uint64) error { 2 // Create a specialized WAL record for ingested SSTables 3 record := &ingestRecord{ 4 paths: paths, 5 seqNum: seqNum, 6 timestamp: time.Now().UnixNano(), 7 } 8 9 // Encode as a special batch entry 10 batch := d.newBatch() 11 for _, path := range paths { 12 batch.logData(InternalKeyKindIngestSST, []byte(path), nil) 13 } 14 15 // Force WAL sync for durability 16 opts := &writeOptions{Sync: true} 17 return d.apply(batch, opts) 18}

If the system crashes before the flush completes, no problem! Replaying the WAL with our added ingested record will recreate the flushable, add it to the flush queue, and the flush will proceed as normal.

Our WAL replay handles ingested SSTables by just recreating the flushable (from the SSTable metadata) and adding it to the flush queue.

1func (d *DB) replayWAL() error { 2 for { 3 record, err := d.readWALRecord() 4 if err == io.EOF { 5 break 6 } 7 8 switch record.Kind { 9 case InternalKeyKindIngestSST: 10 // Reconstruct ingested SSTable from WAL record 11 path := string(record.Key) 12 if err := d.recreateIngestedFlushable(path); err != nil { 13 return err 14 } 15 default: 16 // Handle regular writes 17 if err := d.applyWALRecord(record); err != nil { 18 return err 19 } 20 } 21 } 22 return nil 23} 24 25func (d *DB) recreateIngestedFlushable(path string) error { 26 // Re-read SSTable metadata from disk 27 meta, err := d.loadSSTableMetadata(path) 28 if err != nil { 29 return err 30 } 31 32 // Recreate the flushable and add to queue 33 flushable := d.createIngestedFlushable([]*fileMetadata{meta}, d.currentLogNum()) 34 d.addToFlushQueue(flushable) 35 36 return nil 37}

Step 3: Turn it into a flushable

Now the core part: we wrap the ingested SSTable in an ingestedFlushable and add it to the flush queue.

1func (d *DB) createIngestedFlushable(meta []*fileMetadata, logNum FileNum) *ingestedFlushable { 2 // Sort files by smallest key for efficient iteration 3 sort.Slice(meta, func(i, j int) bool { 4 return d.cmp(meta[i].Smallest.UserKey, meta[j].Smallest.UserKey) < 0 5 }) 6 7 return &ingestedFlushable{ 8 files: meta, 9 cmp: d.cmp, 10 newIters: d.newIters, 11 logNum: logNum, 12 slice: manifest.NewLevelSliceKeySorted(d.cmp, meta), 13 readTime: time.Now(), // Track ingestion time for metrics 14 } 15} 16 17func (f *ingestedFlushable) newIter(o *IterOptions) internalIterator { 18 // Create a mergingIter over all ingested files 19 iters := make([]internalIterator, len(f.files)) 20 for i, file := range f.files { 21 iter, err := f.newIters(file, o, internalIterOpts{}) 22 if err != nil { 23 // Clean up already opened iterators 24 for j := 0; j < i; j++ { 25 iters[j].Close() 26 } 27 return &errorIter{err: err} 28 } 29 iters[i] = iter 30 } 31 32 // Return a merging iterator that provides unified view 33 return newMergingIter(f.cmp, iters...) 34}

The ingested SSTable gets sequence number 15, newer than the memtable's entries (10-14). This ensures proper ordering while making the data immediately visible to reads.

The async flush

Ingestion returns immediately, but in the background, a flush process moves everything in the flushableQueue (both memtables and ingested SSTables) into the LSM tree.

Step 4: Process the queue

The flush system processes entries in strict sequence number order:

1func (d *DB) processFlushQueue() error { 2 d.mu.Lock() 3 defer d.mu.Unlock() 4 5 for len(d.mu.mem.queue) > 0 { 6 entry := d.mu.mem.queue[0] 7 8 // Determine flush strategy based on flushable type 9 switch f := entry.flushable.(type) { 10 case *memTable: 11 // Standard memtable flush to L0 12 return d.flushMemtable(f, entry.logNum) 13 case *ingestedFlushable: 14 // Special handling for ingested SSTables 15 return d.flushIngestedSST(f, entry.logNum) 16 default: 17 return errors.New("unknown flushable type") 18 } 19 } 20 return nil 21}

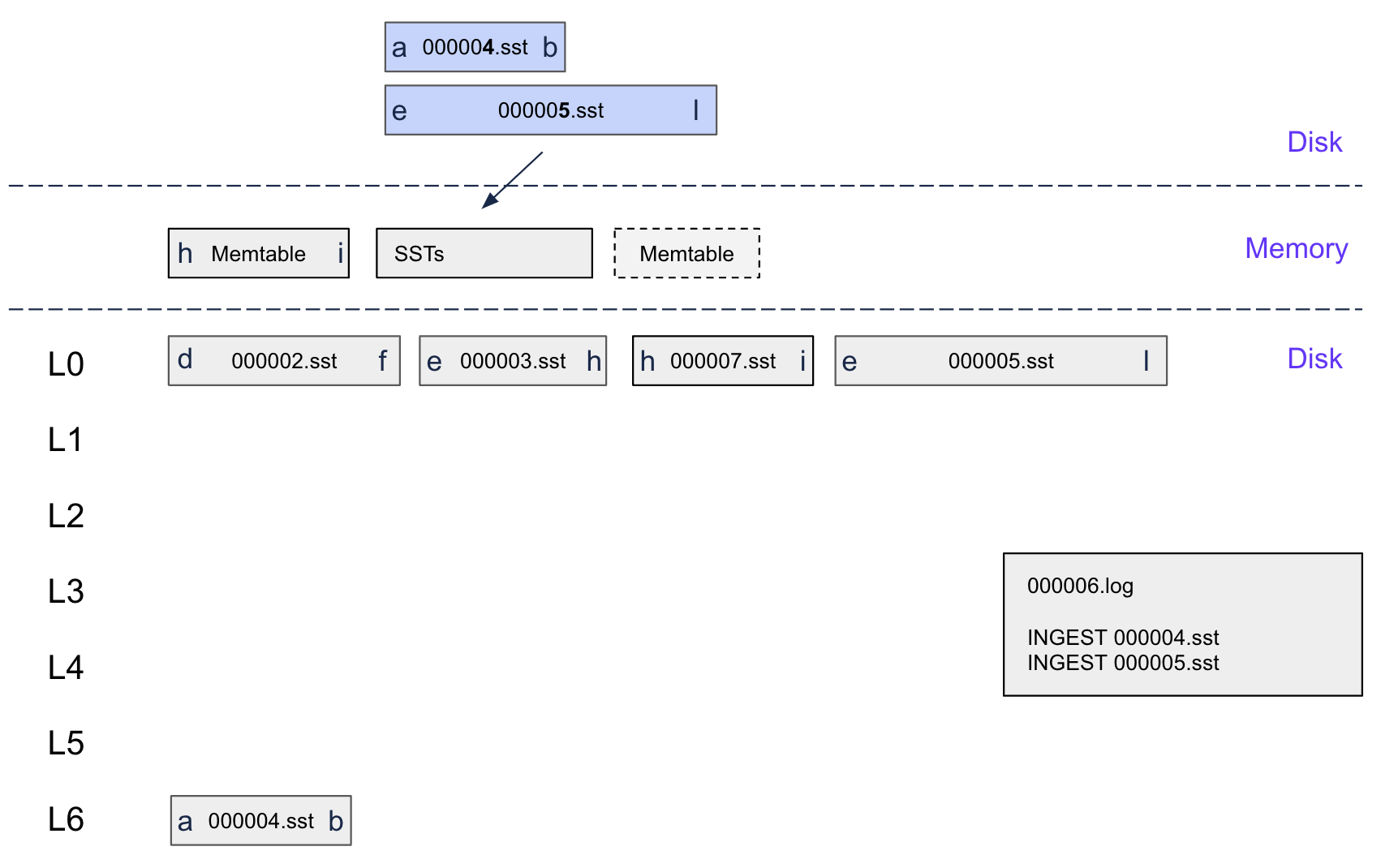

Step 5: LSM Placement

(Note: 000005.sst and 000004.sst are ingested SSTables)

First, the memtable flushes to L0, creating SSTable 000007.sst with keys H-I.

Then, the ingested SSTable's ranges get placed optimally:

- A-B range: No overlaps, goes straight to L6 (zero-copy!)

- E-L range: Overlaps with the flushed memtable, has to go to L0

This differential placement is key – parts of the same ingested SSTable can end up at different levels based on what overlaps.

Unlike memtables that always go to L0, ingested SSTables get placed at their optimal level:

1func (d *DB) flushIngestedSST(f *ingestedFlushable) (*versionEdit, error) { 2 ve := &versionEdit{DeletedFiles: make(map[deletedFileEntry]*fileMetadata)} 3 4 for _, file := range f.files { 5 // Analyze LSM structure to find optimal placement 6 targetLevel := d.pickIngestLevel(file) 7 8 if targetLevel == 0 { 9 // File overlaps with L0, must be placed there 10 ve.NewFiles = append(ve.NewFiles, newFileEntry{ 11 Level: 0, 12 Meta: file, 13 }) 14 } else { 15 // Can be placed directly at target level (zero-copy optimization) 16 ve.NewFiles = append(ve.NewFiles, newFileEntry{ 17 Level: targetLevel, 18 Meta: file, 19 }) 20 } 21 } 22 23 // Atomically update the LSM manifest 24 return ve, d.mu.versions.logAndApply(ve) 25} 26 27func (d *DB) pickIngestLevel(file *fileMetadata) int { 28 // Start from L6 and work upward to find the deepest level with no overlaps 29 for level := numLevels - 1; level > 0; level-- { 30 if d.mu.versions.current.overlaps(level, d.cmp, 31 file.Smallest.UserKey, file.Largest.UserKey, false) { 32 continue 33 } 34 35 // Check if the level above has space (to maintain LSM pyramid shape) 36 if level > 1 && d.levelHasCapacity(level) { 37 return level 38 } 39 } 40 41 // Default to L0 if no deeper placement is safe 42 return 0 43}

Performance

I benchmarked this using synthetic workloads that simulated the worst case – ingested SSTables that overlap with multiple memtables:

1func BenchmarkIngestOverlappingMemtable(b *testing.B) { 2 // Create overlapping memtables with varying degrees of key overlap 3 for _, numMemtables := range []int{1, 2, 3} { 4 b.Run(fmt.Sprintf("memtables=%d", numMemtables), func(b *testing.B) { 5 db := setupTestDB(b) 6 7 // Fill memtables with overlapping key ranges 8 for i := 0; i < numMemtables; i++ { 9 fillMemtableWithKeys(db, 10000, i*5000, (i+2)*5000) 10 } 11 12 // Create SSTable that overlaps with all memtables!! 13 sstPath := createOverlappingSSTables(b, 1000, 7500) 14 15 b.ResetTimer() 16 for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ { 17 err := db.Ingest([]string{sstPath}) 18 require.NoError(b, err) 19 } 20 }) 21 } 22}

The results scaled nicely with the number of overlapping memtables:

| Scenario | Baseline | Flushable SSTables | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overlapping Memtable | 237µs | 126µs | 46.73% |

| 2 Overlapping Memtables | 615µs | 230µs | 62.69% |

| 3 Overlapping Memtables | 1.66ms | 0.41ms | 75.45% |

Where did the speedup come from?

- No more blocking: Ingestion doesn't wait for memtable flushes anymore (saved 200-500ms per memtable)

- Fewer syscalls: No forced fsync operations during ingestion

- Better parallelism: Flushes happen in the background while writes continue

The tradeoff:

By moving ingested SSTables into the flush queue, we shifted work from the ingestion path to the flush path. There's a small overhead during flush:

| Scenario | Baseline | Flushable SST Flush | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 SSTable | 68.5µs | 103.5µs | +51.21% |

| 2 SSTables | 68.6µs | 106.7µs | +55.59% |

| 3 SSTables | 68.2µs | 109.0µs | +59.89% |

But this overhead is asynchronous, happens in the background, and is tiny compared to the 1000µs+ we save during ingestion.

In production, this cut bulk import time by 60%, eliminated write stalls during bulk loading, and made rebalancing much smoother.