Concurrent manual compactions

Segmenting key space and parallelizing execution, 30% perf improvement

This post describes my implementation of concurrent manual compactions in Pebble during my time at Cockroach Labs in 2022.

Before we dive into the details of the project, let’s first understand the storage engine of Pebble, a key-value store inspired by RocksDB/LevelDB and the storage engine for CockroachDB.

Storage Essentials

The core of Pebble is a log-structured merge tree (LSM) with six levels, and an in-memory data structure called the memtable that sits above.

New entries or edits are created as new files, so we can perform sequential IO rather than random IO (faster). These files are called SSTables (Sorted String Tables) and are a list of consecutive key-value pairs sorted in key order and are immutable.

For the sake of explanation, let’s consider a SET and READ operation.

SET:

- An entry is added to the write-ahead-log (WAL) and then added in sorted-order to the memtable.

- In the event of a crash, we can recover the memtable state by replaying the WAL.

- When the memtable reaches a certain size threshold, it is flushed to disk, creating immutable SSTables.

READ:

- Because we don't know which SSTable has the latest value, we have to check each SSTable in order. This is known as read amplification.

- We check the entries in reverse chronological order (top down with regards to the LSM), thus starting with the memtable and ending in L6.

- An optimization to reduce read amplification is to have a bloom filter for each SSTable, which is a probabilistic data structure that tells us if a key is present in the SSTable.

Ideally, we want to keep our LSM in a pyramid shape (▲) to minimize:

- read amplification (the amount of data read from disk), achieved by having the fewest number of SSTs to check

- write amplification (the amount of data written to disk), achieved by having the fewest number of SSTs to compact (more below)

- space amplification (the amount of data stored on disk), achieved by having the fewest number of SSTs on disk

To achieve this, we want to combine redundant SSTs and push them to lower levels; this is done through compactions.

Manual Compactions

Compactions are done both automatically and manually, where the former is done in the background and the latter is ad-hoc. We will be discussing manual compactions.

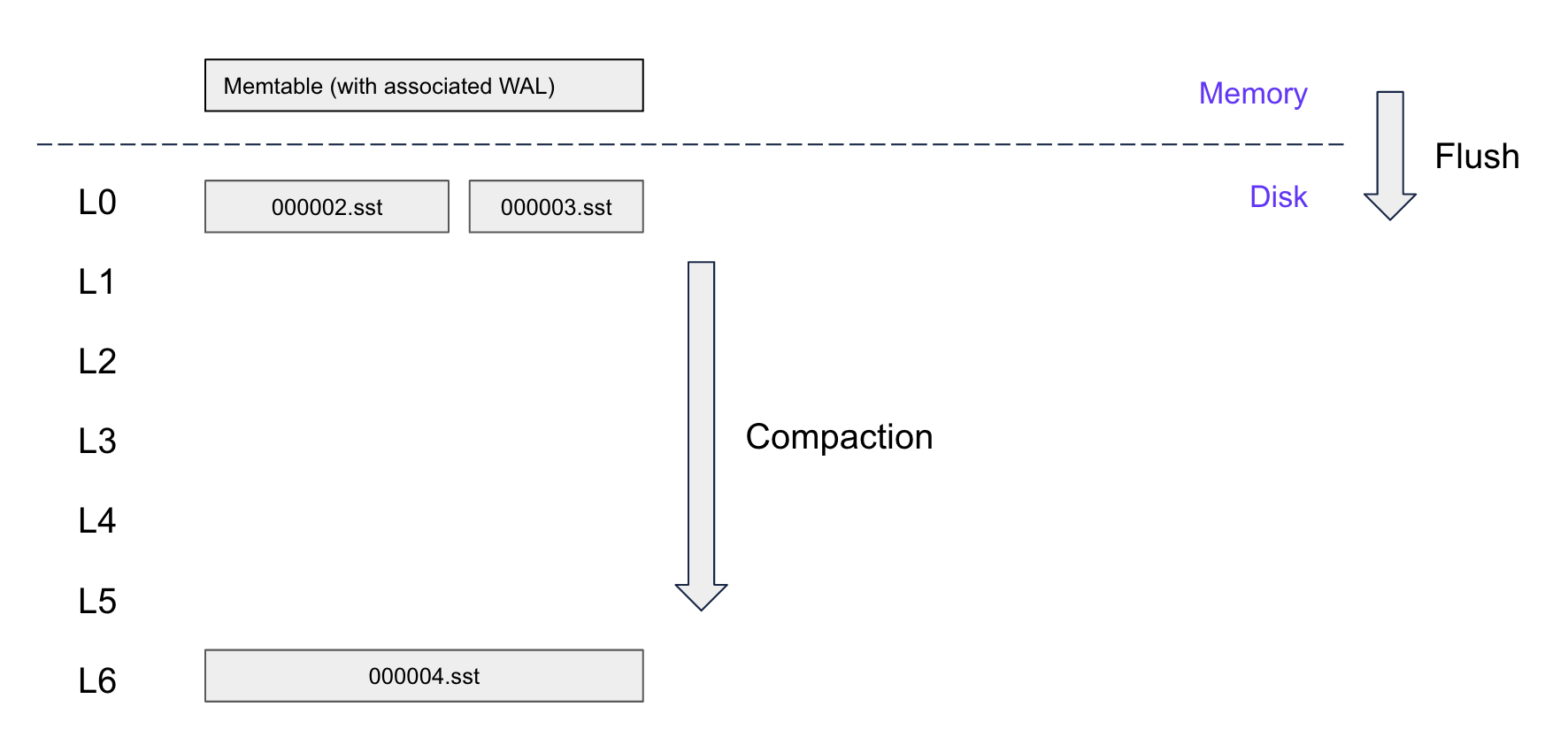

When a workload adds files to L0 faster than they can be compacted out, a large number of files accumulate in L0 and lead to an inverted LSM. A manual compaction can be used in this scenario to help return the LSM to a pyramid shape.

CockroachDB allows running manual compactions either through the SQL shell or through the Pebble instance directly.

Online (Blocking SQL command):

1SELECT crdb_internal.compact_engine_span(<nodeID>, <storeID>, decode('00', 'hex'), decode('FFFFFFFF', 'hex'));

Offline (node is taken offline):

1./cockroach debug compact

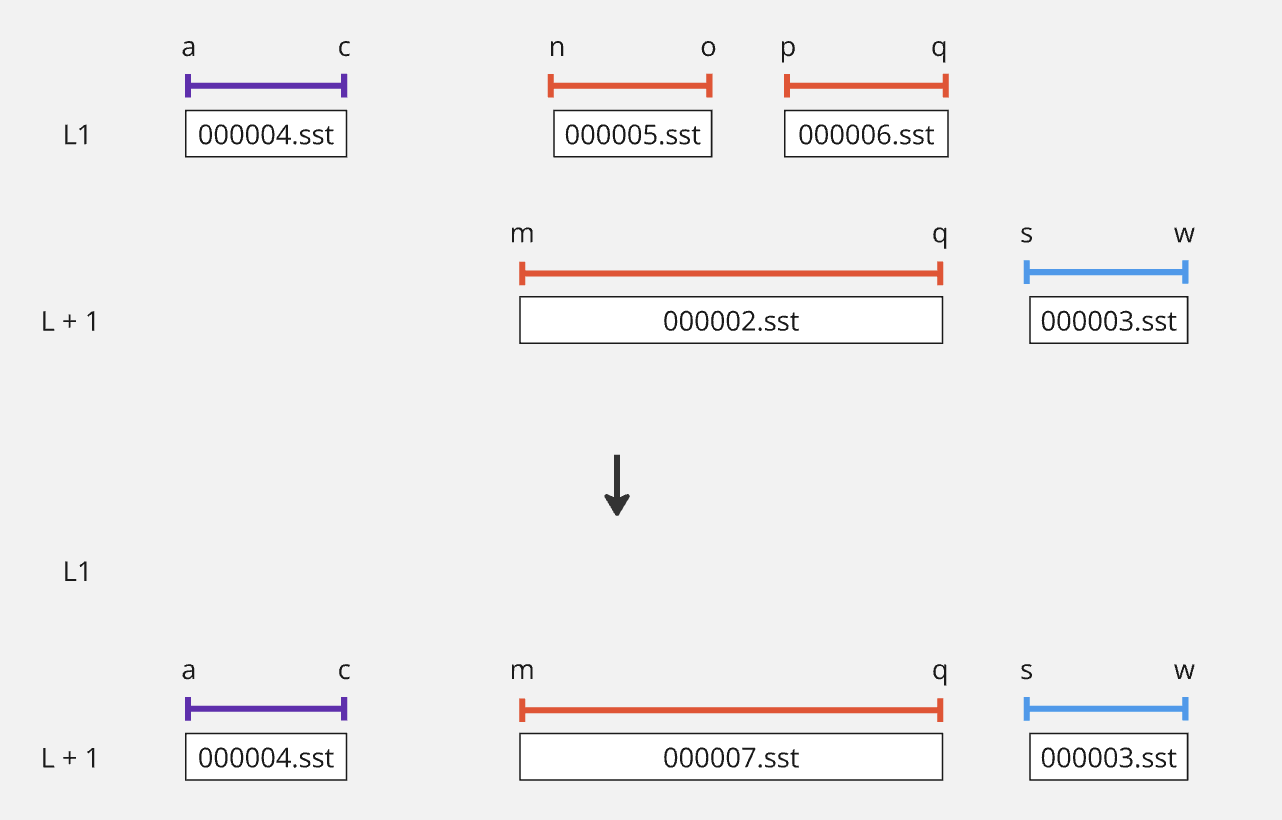

Let's consider a simple example of a manual compaction:

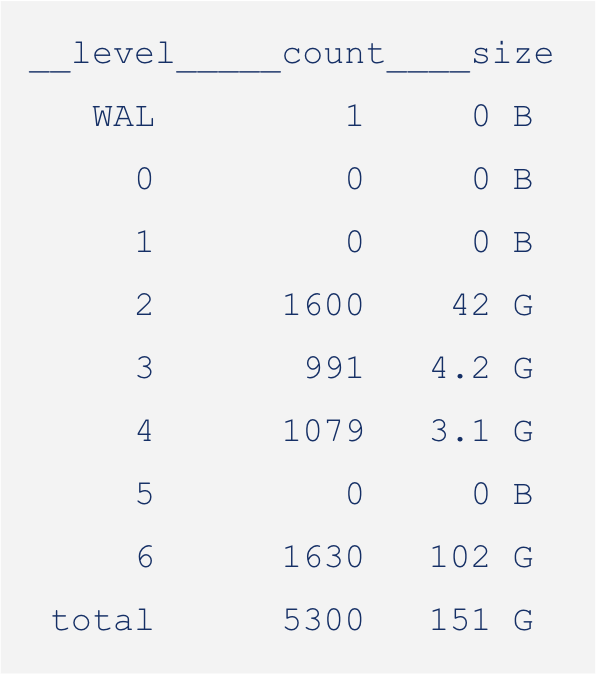

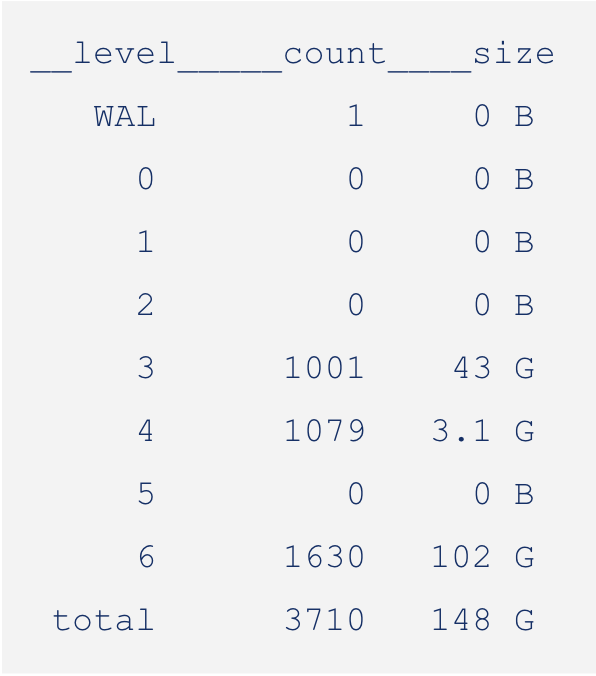

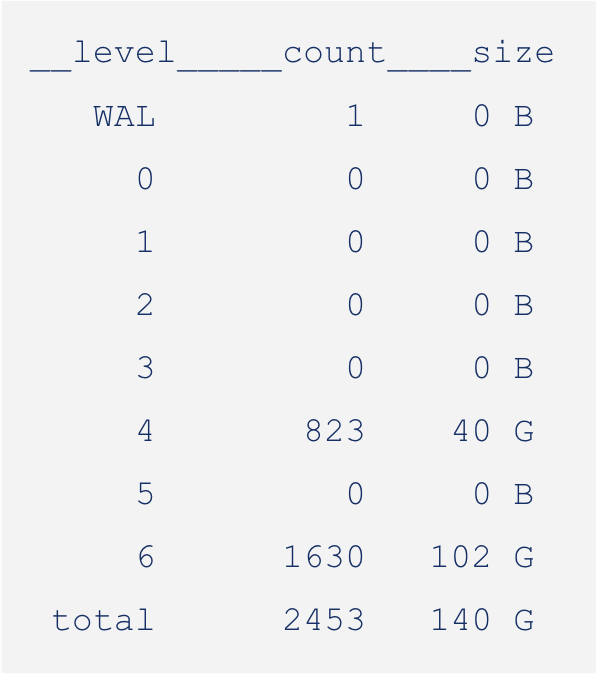

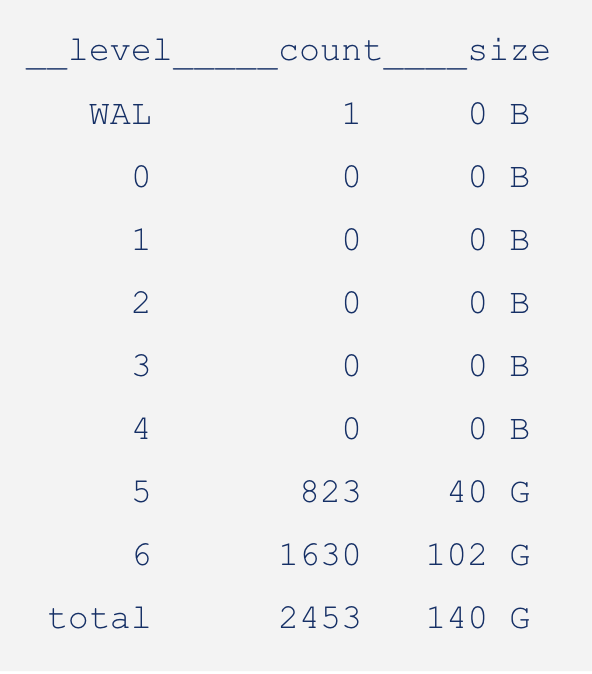

In the above sequence of images, you can see the manual compaction proceed from L0 to L1, L1 to L2, and so on. While compacting, the size of the LSM reduces as we combine redundant keys and push them to lower levels.

Motivation

Before my changes, manual compactions were done serially level by level, i.e. L0 to L1, then L1 to L2, etc. When a node is taken offline, we don't need to be considerate for any foreground traffic – thus allowing us to make full use of the available system resources.

As an anecdote, during this project, we encountered a customer who was manually compacting a database several petabytes in size. The process had been running for 6 days(!), highlighting the urgency of the issue.

Implementation

The main performance optimization opportunity was to parallelize the compactions. To do this, we'd need to:

- Segment the key space into non-overlapping key ranges

- Execute the compactions in parallel

- Synchronize their completion

By segmenting the key ranges, we can ensure that only one concurrent compaction is operating (reading/writing) on a particular key range at a time.

Here is a stub of the method we will incrementally fill in:

1func (d *DB) manualCompact(start, end []byte, level int, parallelize bool) error { 2 // 1. Split the compaction range into non-overlapping key ranges 3 4 // 2. Execute the compactions in parallel 5 6 // 3. Synchronize their completion 7}

1. Key-space Segmentation

Pebble has a function to calculate the distinct key ranges across 2 levels: calculateInuseKeyRanges (implementation).

With that, we can split up the compaction range of a particular level into non-overlapping key ranges:

1// splitManualCompaction splits a manual compaction over [start,end] on level 2// such that the resulting compactions have no key overlap. 3// 4// d.mu must be held when calling this. 5func (d *DB) splitManualCompaction( 6 start, end []byte, level int, 7) (splitCompactions []*manualCompaction) { 8 curr := d.mu.versions.currentVersion() 9 endLevel := level + 1 10 if level == 0 { 11 // If we are compacting from L0, compact to Lbase instead of level+1 12 endLevel = d.mu.versions.picker.getBaseLevel() 13 } 14 15 // Get non-overlapping key ranges 16 keyRanges := calculateInuseKeyRanges(curr, d.cmp, level, endLevel, start, end) 17 18 for _, keyRange := range keyRanges { 19 splitCompactions = append(splitCompactions, &manualCompaction{ 20 level: level, 21 // Use a channel to signal completion, more on this later! 22 done: make(chan error, 1), 23 start: keyRange.Start, 24 end: keyRange.End, 25 split: true, 26 }) 27 } 28 29 return splitCompactions 30}

We call the above method in db.manualCompact:

1func (d *DB) manualCompact(start, end []byte, level int, parallelize bool) error { 2 d.mu.Lock() 3 4 var compactions []*manualCompaction 5 if parallelize { 6 // Get non-overlapping compactions 7 compactions = append(compactions, d.splitManualCompaction(start, end, level)...) 8 } else { 9 compactions = append(compactions, &manualCompaction{ 10 level: level, 11 done: make(chan error, 1), 12 start: start, 13 end: end, 14 }) 15 } 16 17 // Execute the compactions... 18}

2. Parallel Execution

We now have multiple compactions for a single level that don't have overlapping key ranges, let's execute them!

To execute the compactions, we add them to a queue and then attempt to schedule them for execution:

1func (d *DB) manualCompact(start, end []byte, level int, parallelize bool) error { 2 d.mu.Lock() 3 4 var compactions []*manualCompaction // non-overlapping compactions from previous step 5 6 d.mu.compact.manual = append(d.mu.compact.manual, compactions...) 7 d.maybeScheduleCompaction() 8 d.mu.Unlock() 9}

maybeScheduleCompaction will schedule the compactions for execution.

pickManual returns a *pickedCompaction representing a compaction that has been picked for execution,

with verified compaction input/output levels and protection against running a conflicting compaction.

That *pickedCompaction is then turned into a *compaction which can be directly executed by Pebble.

1// maybeScheduleCompaction schedules a compaction if necessary 2// 3// d.mu must be held when calling this. 4func (d *DB) maybeScheduleCompaction() { 5 ... 6 7 for len(d.mu.compact.manual) > 0 && d.mu.compact.compactingCount < d.opts.MaxConcurrentCompactions { 8 manual := d.mu.compact.manual[0] 9 10 // Check if we can run the compaction 11 pc, retryLater := d.mu.versions.picker.pickManual(env, manual) 12 if pc != nil { 13 c := newCompaction(pc, d.opts, env.bytesCompacted) 14 15 // Pop from the queue 16 d.mu.compact.manual = d.mu.compact.manual[1:] 17 18 // Add to currently executing compactions 19 d.addInProgressCompaction(c) 20 21 // Concurrently execute the compaction 22 go d.compact(c, manual.done) 23 } else if !retryLater { 24 // Drop the compaction 25 d.mu.compact.manual = d.mu.compact.manual[1:] 26 manual.done <- nil // Don't forget to send to the channel! 27 } else { 28 ... 29 } 30 } 31 32 ... 33}

d.compact runs the picked concurrent manual compaction and sends to the done channel to signal completion.

3. Synchronize completion

With manual compactions we need to ensure all compactions for a particular level complete before proceeding to the next level. As mentioned above we use a go channel to accomplish this.

This completes our manualCompact function:

1// Compacts the given level of the LSM between start and end. 2func (d *DB) manualCompact(start, end []byte, level int, parallelize bool) error { 3 d.mu.Lock() 4 5 // If level is empty, return early 6 7 var compactions []*manualCompaction 8 if parallelize { 9 // Get non-overlapping compactions 10 compactions = append(compactions, d.splitManualCompaction(start, end, level)...) 11 } else { 12 compactions = append(compactions, &manualCompaction{ 13 level: level, 14 done: make(chan error, 1), 15 start: start, 16 end: end, 17 }) 18 } 19 20 d.mu.compact.manual = append(d.mu.compact.manual, compactions...) 21 d.maybeScheduleCompaction() 22 d.mu.Unlock() 23 24 // Each of the channels is guaranteed to be eventually sent to once. After a 25 // compaction is possibly picked in d.maybeScheduleCompaction(), either the 26 // compaction is dropped, executed after being scheduled, or retried later. 27 // Assuming eventual progress when a compaction is retried, all outcomes send 28 // a value to the done channel. Since the channels are buffered, it is not 29 // necessary to read from each channel, and so we can exit early in the event 30 // of an error. 31 for _, compaction := range compactions { 32 if err := <-compaction.done; err != nil { 33 return err 34 } 35 } 36 return nil 37}

Finally, we run the concurrent manual compactions level by level in the main compaction method:

1// Compacts the entire LSM between start and end. 2func (d *DB) Compact(start, end []byte, parallelize bool) error { 3 d.mu.Lock() 4 5 // Find Lbase (lowest non-empty level of LSM) 6 maxLevelWithFiles := 1 7 for level := 0; level < numLevels; level++ { 8 overlaps := // if SSTs in `level` have overlap with start-end 9 if !overlaps.Empty() { 10 maxLevelWithFiles = level + 1 11 } 12 } 13 14 // Determine if any memtable overlaps with the compaction range. We wait for 15 // any such overlap to flush (initiating a flush if necessary). 16 17 d.mu.Unlock() 18 19 for level := 0; level < maxLevelWithFiles; { 20 if err := d.manualCompact(iStart.UserKey, iEnd.UserKey, level, parallelize); err != nil { 21 return err 22 } 23 level++ 24 25 if level == numLevels-1 { 26 // A manual compaction of the bottommost level occurred. 27 // There is no next level to try and compact. 28 break 29 } 30 } 31 return nil 32}

Benchmarking

While it would have been ideal to run these benchmarks programmatically, the precondition for the use of a manual compaction is an inverted LSM.

Thus, I seeded an LSM with the YCSB F workload which inserts keys following a zipf distribution (higher frequency of key ranges). Workload F is a write-heavy workload and is known to lead to an inverted LSM when using a large number of concurrent writers.

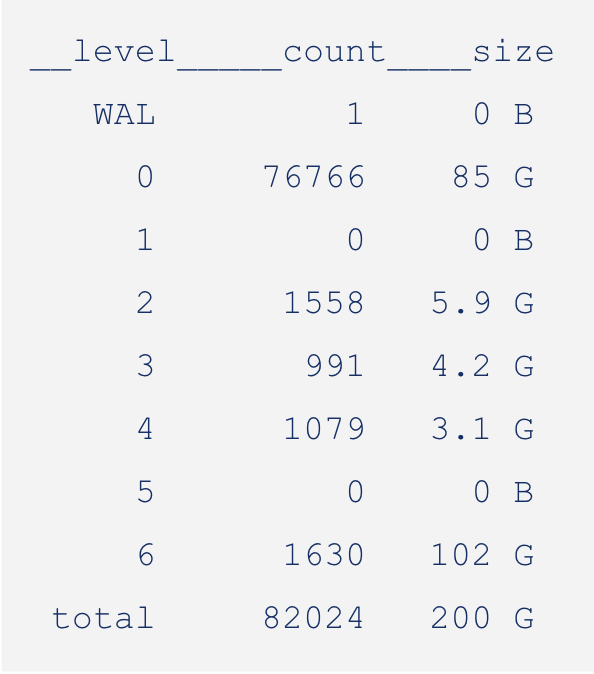

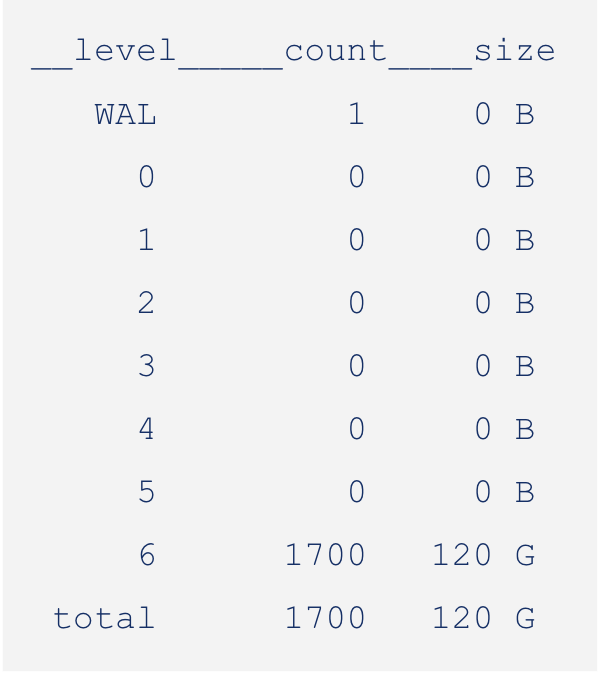

Here is the LSM after seeding:

1__level_____count____size___score______in__ingest(sz_cnt)____move(sz_cnt)___write(sz_cnt)____read___r-amp___w-amp 2 WAL 3 138 M - 0 B - - - - 138 M - - - 0.0 3 0 69428 84 G 3.02 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 4 1 0 0 B 0.00 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 5 2 2478 9.7 G 5.45 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 6 3 1975 12 G 5.72 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 7 4 1497 15 G 5.73 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 8 5 961 18 G 0.87 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 9 6 703 15 G - 0 B 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0 B 0 0.0 10 total 77042 154 G - 138 M 0 B 0 0 B 0 138 M 0 0 B 0 1.0 11 flush 0 12compact 0 583 G 0 B 0 (size == estimated-debt, score = in-progress-bytes, in = num-in-progress) 13 ctype 0 0 0 0 0 (default, delete, elision, move, read) 14 memtbl 39 144 M 15zmemtbl 0 0 B 16 ztbl 0 0 B 17 bcache 0 0 B 0.0% (score == hit-rate) 18 tcache 0 0 B 0.0% (score == hit-rate) 19 snaps 0 - 0 (score == earliest seq num) 20 titers 0 21 filter - - 0.0% (score == utility)

You can see that L0 alone makes up more than half of the total size of the LSM. This is a clear indication of an inverted LSM.

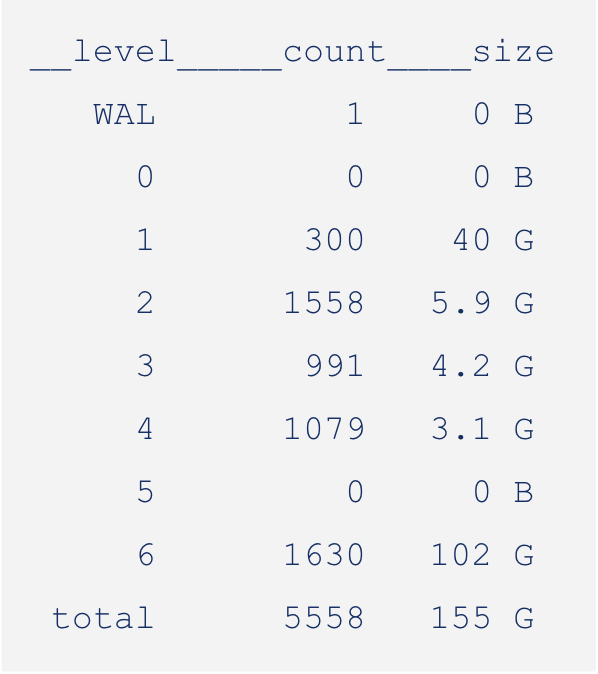

After seeding an inverted LSM of around 150 GB, I ran the manual compactions with and without parallelization:

| Implementation | Times |

|---|---|

| Serial | Real: 550m32.809s User: 589m52.219s Sys: 36m25.205s |

| Concurrent | Real: 384m56.152s User: 373m0.258s Sys: 28m25.139s |

The results were promising with a roughly 30% improvement in compaction time!

While the performance improvement is significant, the compaction logs when benchmarking revealed that the majority of the time is spent in L0 to Lbase compactions. My implementation was extended to use L0 sublevels to further parallelize compactions in L0, yielding an additional 92% improvement in overall compaction time! Kudos to Arjun Nair for the follow-up work.

Conclusion

All in all, this project was my first large contribution to CockroachDB and the performance improvements were significant and impactful. Compactions are still an active work area in Pebble and I’m excited to see the future optimizations that the team will come up with.